Jungle Boogie

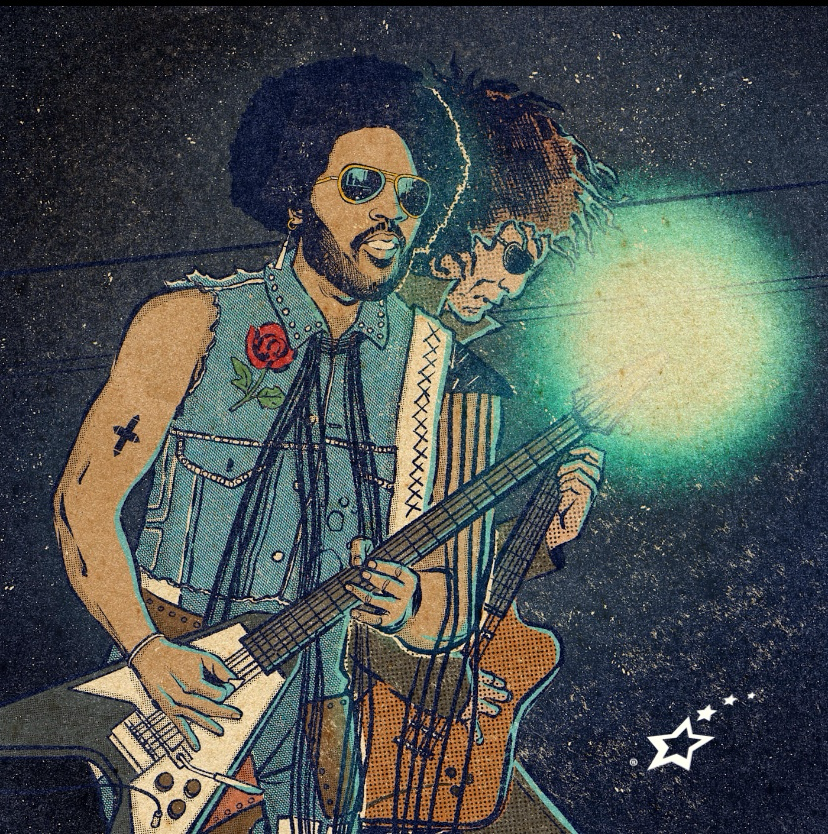

Lenny Kravitz & Craig Ross

Feature Interview

“I’m sorry, he’s just running 10 more minutes late,” says the Atlantic Records PR exec. “He’s still on a water taxi.”

Bloody cab drivers—always giving Lenny grief.

Back in the eighties, racist New York cabbies would hear the budding musician whistle, take one look at his dreads, and just keep driving.

A snub that famously inspired the song Mr. Cab Driver on Lenny Kravitz’s debut album, Let Love Rule. Eight albums later, after winning four Grammys and selling over 35 million records, Kravitz is more accustomed to getting picked up in black limos than yellow cabs. But here he is, delayed for his interview in support of his new album, Black & White America, put in an imposition by yet another taxi—albeit this time on water.

“I’m in the Bahamas, so no, I don’t have that problem with cab drivers here,” says Kravitz, now back on terra firma, moseying down a quiet street on the island of Eleuthera. “Back in the US, some still have that way about them, but, you know, times are different now. They’re getting better with each generation.”

Kravitz is referring to the recent transition his homeland has gone through, with Barack Obama installed as president, proving that having a mixed heritage is no longer an automatic barrier to personal advancement in the establishment of American society.

At the time of Obama’s inauguration—Obama, like Kravitz, an American who shares both Black and white heritage—Lenny was ensconced in the studio, attempting to complete his long-awaited album, Negrophilia. Known amongst his fans as “The Funk Record,” it was a completely different album from the one he is about to release.

“I came to the Bahamas… and I began hearing all this new music.”

“Negrophilia is very close to me, and I will finish that. But I had new inspiration when I came out to the Bahamas. I secluded myself, stayed here for almost two years, got to a very peaceful place, and I began hearing all this new music,” says Kravitz, who has previously surfed the flood of inspiration away from Negrophilia before, to record the more rock-infused Baptism album back in 2004. He and his band—including longstanding guitar player Craig Ross—had begun working on it during a three-month sabbatical after attending Edgefest in New Orleans.

“We booked a studio and just started messing around,” says Craig Ross, who also has a pad in the Bahamas, about ten minutes from Kravitz’s place. Currently sporting a shorter haircut than he’s known for (“The frizzy ’do relaxes with the rest of me when I’m here,” he tells me), Ross adds that he hopes to finish Negrophilia with Lenny one day. “It’s super raw, and it’s super funky. We were going to work on it this time, but, as you know, the music took a turn.”

“When the inspiration hits, you either go with your ego and your plan, or just go with what feels right at the time,” explains Lenny, who, having had the musical idea for the horn-backed soul song Push (the closing track), began writing and recording Black & White America in earnest—an album he believes to be his best work to date, and one which, ironically, features some of Lenny’s funkiest stuff in over a decade.

On the 1 is the standout, project centrepiece Life Ain’t Better Than It Is Now, which works the groove as hard as a sweat-drenched James Brown whilst maintaining an upbeat outlook. Superlove sounds like Ernie Isley has dropped by to jam with Bootsy’s Rubber Band, and the album is suitably kicked off, in socially conscious funky soul style, with the defiant Black & White America, which includes lyrics born out of Lenny’s own experiences growing up in supposedly cosmopolitan and liberal New York City as the child of an interracial couple (Lenny’s mum was actress Roxie Roker, and his dad, NBC TV producer Sy Kravitz). Alluding to memories that prove bigots—no matter their creed or colour—are actually united in their own ignorance.

“I had no idea about race until I was in the first grade,” remembers Lenny. “I understood that my parents were different from each other, but I didn’t think that meant anything. I was used to seeing a lot of interracial couples at my house because there was a lot of integration going on amongst my parents’ friends, which included artists, celebrities, and so forth. So I’d see every race you could imagine and didn’t think about it—people are different, that’s life.

"Then I showed up at school, and on the first day, some kid ran up to us, pointed his finger, and yelled, ‘Your father’s white!’ He made this big remark in the hallway, and I was like, ‘What was that all about?!’ I really didn’t have any idea what him being white had to do with anything. That’s when it started, in public. In my home, it was beautiful and healthy—I was taught to respect both sides of my culture.”

The variety of culture meant that Lenny was exposed to a diverse range of music, first getting into soul and funk in New York, before moving to Los Angeles to become introduced to rock music at Junior High.

Black & White America harks back to Lenny’s first three albums, reflecting his diversity of taste whilst still being anchored in slop. So, there may be the Jay-Z-featured R&B of Boongie Drop (“boongie” means arse in the Bahamas) or the sing-along pop ’n’ roll pep of second single Stand, but there’s plenty of soul too.

Like with his recent productions on Labelle (Lenny says: “I really wish that I was able to do the whole Back to Now album—I had a vision for making the lost Labelle record. I wanted them to sound like songs discovered after being locked in a Labelle vault”) and previous soul hits Heaven Help and It Ain’t Over ’Til It’s Over, Lenny’s more than earned his soulboy stripes. Along with the title track, there’s a handful of soul gems: the aforementioned Push, a falsetto-sung inner-city blues called Liquid Jesus, recorded whilst Kravitz finished the album off in Paris, and the wistful and reflective Looking Back on Love.

“That was written at Gregory Town (the studio I own in Eleuthera), one afternoon when I was sat at a Fender Rhodes. It literally came from my life—all of the beautiful people that I’ve encountered and what I’ve learnt from them,” Lenny explains.

In contrast, the album was preceded by the primal, heavy guitar and horn-laced killer Come On Get It, used to promote the start of the NBA season on US TV, which screams the line, “I feel like a canine, come on, come on and get it!”—suggesting that, at 47 years old, Lenny is still living, as he puts it in another song title, the Rock Star City Life.

Is there still an abundance of Lenny-lovin’ groupies hanging out backstage, trying to score a one-on-one session?

“Aaaah,” says Lenny, almost misty-eyed. “If I wanted to, I could. But I guess now it would be more of a rock-star-jungle-life.” Lenny laughs. “If I want to, it’s available. It’s probably still there, sure, but I don’t go that way. After the shows, I head back to the hotel, and I have my own rules—I get rest. I do what I gotta do.”

According to Ross, there are still shenanigans on the road—streakers at gigs and all that kind of madness—but by the sounds of it, for Lenny at least, it’s a cup of PG Tips in the hotel room. Maybe with two sugars if he’s feeling adventurous.

Ross remembers the warm-hearted and anthemic, gospel choir-backed The Faith of a Child as being more indicative of the overall atmosphere when recording the album. “Herman Leonard (legendary photographer) came to the studio while we were doing The Faith of a Child. He did those black-and-white pictures with the smoke and the jazz icons, y’know? He was very ill and didn’t have that much longer with us, but Lenny decided to fly him and his family to the Bahamas so he could do some pictures, he could rest, he could relax, and they could all enjoy a vacation.”

Kravitz intended the album to be completed with a work/life balance, with the band relocating to the Bahamas. One of the reasons Henry Hirsch wasn’t involved this time is that he didn’t fancy upping sticks and moving away from New York to live near a jungle in paradise.

“We made a conscious effort,” says Ross, “to try and mix life with recording, as opposed to just work. We wanted to live a little bit before the whole thing starts over again and you just head out on the road. This time around, we got to record at our leisure, and I think the music reflects the fact that everything was so fun and happy.”

“It was a revelation to me,” adds Lenny. “The morning I wrote Life Ain’t Better Than It Is Now, I woke up in my trailer on the beach and just ran to my studio. Defining my place, where I am in my life now, and being really comfortable with who I am, and, you know… just content.”

I guess the dark funk album will probably have to wait just a little longer.

“Black & White America”

is available on Roadrunner Records

Words by Dan Dodds | Art by Longnose

A shortened version was originally published in Echoes Magazine, Sept 2011